- Home

- Antoni Libera

Madame Page 2

Madame Read online

Page 2

In the end, our role in these events was more grotesque than ignominious, more farce than defeat. We played what we wanted, but the context was absurd. For instance, ‘Georgia’ came on the heels of a histrionic collective rendition of Mayakovsky’s ‘Left Forward’, and blues followed the recital, in a series of hysterical shrieks, of verses depicting the horrifying plight of workers in America, where, it was confidently stated, ‘each day some unemployed / jump headlong from the bridge / into the Hudson’. The whole thing, in short, was preposterous, and everyone, the audience as well as ourselves, felt this. How, in such conditions, could one even entertain the illusion that one was creating history or participating in momentous events?

Once a small flame of hope did briefly appear. But it flickered for only an instant, and the circumstances were exceptional.

We were indulged with various diversions in those days, and one of the most tedious was the annual festival of school choirs and vocal groups. It always took place, according to the rule, in the school whose group had won the first prize, the notorious Golden Nightingale, the preceding year. To our misfortune, it so happened that this particular year the pathetic trophy had gone to a group from our school – the ludicrous Exotic Trio, whose speciality was Cuban folklore. Their regrettable triumph meant that the task of organising the festival now fell to us. This was a monstrous headache, involving ‘community work’ after class and, most nightmarish of all, three days of auditions culminating in a concert given by the winners, at which attendance, as a sign of the hosts’ hospitality, was obligatory.

The reality surpassed our worst expectations. This was owing principally to our singing instructor, the terror of the school. Known as ‘the Eunuch’ because of his reedy voice (a ‘Heldentenor’, by his own description) and his old-bachelor ways, he was a classic neurotic, with a tendency toward excessive enthusiasm and an unswerving conviction that singing – classical singing, naturally – was the most glorious thing on earth. He was the object of endless jokes and ridicule, but he was also a figure of fear. When something had enraged him beyond the limits of his endurance he was capable, at the height of his fury, of lashing out and doing us physical harm. Worst of all, he could utter threats so macabre that, although we knew from experience they would not be carried out, the very sound of them made the world go dark before our eyes. The one he resorted to most often went like this: ‘I’ll rot in prison for the rest of my days, but in a moment, with the aid of this instrument’ – whereupon he would take a penknife out of his pocket and flick it open to reveal the blade – ‘with the aid of this blunt instrument here, I’ll hack off someone’s ears!’

And this maniac, this raving lunatic, to put it mildly, was to be in charge of the festival. What this meant in practice may easily be imagined. For the duration of the affair he became the most important figure in the school. This was his festival; these were the days of his triumph. They were also, for him, as the person responsible for the whole thing, days of great stress. He prowled the corridors in a state of feverish excitement, observing everything, poking his nose into everything, wanting to choreograph our every move; after classes he proceeded, with relish, to torment the choir with hours of practice. Everyone was thoroughly sick of him and we longed for the day when this purgatory would come to a blessed end.

By the last day of the festival most of the students were showing symptoms of profound depression and went about in an almost catatonic stupor. The permanent, oppressive presence of the demented Eunuch, the constant flow of new decisions, the endless chopping and changing, the whole accompanied, for hours on end, by the dreadful howling of choirs in full flow – all this tried our endurance to its limit. At last, however, the blessed end arrived. The last notes of some exalted song performed by the winners of this year’s Nightingale resounded and died away; the honourable members of the jury made a grand exit in stately procession; and the students, left to their own devices, with just the chairs to be put away and the stage to be swept, gave way to uncontrollable euphoria.

I had been about to close the piano lid when for some reason I began instead to sound out, rhythmically, four descending notes in a minor key, a simple arrangement that was the typical introduction to many jazz classics, among them Ray Charles’s famous ‘Hit the Road Jack’. My unthinking, barely conscious, repeated action had a spectacular and quite unexpected effect. The crowd of students milling about cleaning up the room immediately took up the rhythm; people started to clap and stamp their feet. After that, events took their unstoppable course. The three other members of the Modern Jazz Quartet, feeling the call of blood, launched themselves upon their instruments. The double bass was the first, plucking out the same four notes, eight quavers in quadruple time. Next on stage was the percussionist; with lightning speed he threw the covers off his instruments, flung himself at his drums and, after a few energetic drumrolls and strikes on his cymbals as an entrée, began, in an attitude of great concentration, his head to one side, to pound out a four-four basso continuo. Then – at first distantly, still from within the instrument cupboard – the trumpet came in, joining us in several repeats of those first four electrifying notes; and when the trumpeter at last appeared on stage, to screams of ecstasy and whoops of joy, he sounded the first bars of the theme.

Everyone went berserk. People began to sway, twitch, twist and contort themselves to the music. And then someone else, a boy who had been looking after the technical side of things, leapt up onto the stage. He pulled up a chair for me (thus far I’d been playing standing up), stuck a pair of sunglasses on my nose to suggest a resemblance to Ray Charles, pushed a microphone up to my lips and said in a passionate whisper, ‘Let’s have some vocal! Come on, don’t be shy!’

Who could resist such an enticement, a plea so eloquent with yearning, brimming with the will of an inflamed crowd? Its urgency was stronger than the choking shame in my throat. I squeezed my eyes shut, took a breath and rasped out into the microphone:

Hit the road Jack,

And don’t you come back no more . . .

And the frenzied, dancing crowd came in with perfect timing. Like a well-rehearsed ensemble they took up the words, endowing them with new meaning and determination:

No more no more no more!

English was not our school’s strong point, and hardly anyone understood what the song was about, but the force of those two words, that ‘no more’ so sweet to the Polish ear, advancing rhythmically up the rungs of a minor scale in a row of inverted triads at the fourth and the sixth, was clear to all. And the crowd took up the chant fully aware of its significance.

No more! Enough! Never, never again! No more howling; no more having to sit and listen. Down with the festival of choirs and vocal groups! To hell with them all! Damn the Golden Nightingale, damn the Exotic Trio, may they vanish from the face of the earth! Damn the Eunuch, may he rot in hell! Don’t let him come back no more . . .

No more no more no more!

And as the crowd was chanting these words for the umpteenth time, in an unrestrained, ecstatic frenzy of hope and relief, there burst into the room, like a ballistic missile, our singing instructor – puce with rage and squawking in his reedy voice, ‘What the bloody hell is going on here?!’

And then a miracle happened – one of those miracles that usually occur only in our imaginations or in a well-directed film, one of those rare things that happen perhaps once in a lifetime.

As anyone who remembers Ray Charles’s hit knows, at the last bar of the main thematic phrase (its second half, to be precise), on the three syncopated sounds, the blind black singer, in a dramatic, theatrically breaking and swooping voice, asks his vocal partner, a woman throwing him out of the house, the intriguingly ambiguous question, ‘What you say?’ This question-exclamation, most likely because it ends on the dominant, is a kind of musical punchline, one of those magic moments in music for which we unconsciously wait and which, when it comes, evokes a shiver of singular bliss.

Now it so happened t

hat the Eunuch’s blood-curdling scream fell precisely at the end of the penultimate bar. I had less than a second to make up my mind. I hit the first two notes of the last bar (another repeat of the famous introduction) and, twisting my face into the mocking, exaggerated grimace assumed by people pretending not to have heard what was said, crowed out with that characteristic rising lilt, in the general direction of the Eunuch, standing now in the middle of a stunned and silent room, ‘What you say?!’

It was perfect. A roar of laughter and a shiver of cathartic joy went through the room. For the Eunuch it was the last straw. With one bound he was at the piano and had launched himself at me. He kicked me roughly off my chair, banged shut the piano lid and hissed out one of his horrifying threats: ‘You’ll pay dearly for this, you little snot! We’ll see who has the last laugh! You’ll be squealing like a stuck pig by the time I’m finished with you. In the meantime, I’ll tell you right now that you’ve just earned yourself an F in singing, and I really don’t see how you can change that before the end of the year.’

That was the last performance of the Modern Jazz Quartet. The following day it was officially dissolved by the school authorities, while I, as an additional reward for my brilliant solo (and it was brilliant, whatever else could be said about it), was favoured with a D in discipline.

All the World’s a Stage

The brief life of our ensemble, like the incident which brought it to a definitive close, seemed to confirm our teachers’ warnings against attempting to emulate former pupils. Here was a tale strikingly like their reminiscences of the past, full of potential colour and spice, just waiting to be brought out in the telling; but the reality was flat, and then silly, and finally, after one moment of glory, when for an instant it sparkled and shone, abrupt and ignominious in its ending.

Yet I didn’t give up. The following year I tried again to forge some magic from the drab reality around me.

It was the time of my first fascination with the theatre. For several months I’d had no interest in anything else. I knew what was playing in every theatre in town; I even went to some plays twice. Like a professional drama critic, I never missed an opening night. I also read endless numbers of plays, devoured all the theatrical magazines I could lay my hands on, and studied the biographies of famous actors and directors.

I was captivated. The tragic and comic fates of dramatic heroes, the beauty and talent of the actors, the élan with which they threw themselves into their scenes and recited their soliloquies, the mysterious half-light and the dazzling glare, the darkness, the backstage secrets, the gong that rang before the act began, and then the joyful conclusion – the audience applauding, the actors, including those whose characters had just died, taking their bows – this whole world of illusion had me under its spell. In those days I could have stayed in the theatre forever.

I decided to see what I could achieve. I wanted to know what it felt like to be up there on the stage, captivating the audience, mesmerising them with eyes and voice and force of expression: what it was like to act, to put on a show. Heedless of the still recent fate of the Modern Jazz Quartet and the troubles it had entangled me in, I set about organising a school drama circle.

The path I was taking wasn’t strewn with roses. On the contrary, it bristled with difficulties and pitfalls far more treacherous than those I’d encountered playing jazz. Playing an instrument, at any level, presupposes certain well-defined and measurable skills; the very possession of them is a guarantee of results, however basic. But the art of theatre is deceptive. While ostensibly much more accessible, it requires, if it is to bear its magic fruit, enormous amounts of work and skills of a very particular kind; otherwise it becomes, insidiously, a source of ridicule. So I had to keep a tight hold on the reins if the spirit of disenchantment was not to paralyse me, for I was involving myself in something which, while diverging considerably from my hopes and dreams, exposed my love for the divine Melpomene to the harshest trials.

Anyone who has ever been in a play knows how rehearsals, particularly walk-throughs, can sap morale: how easily every shortcoming – lack of sets and costumes, absence of lights and props, lines imperfectly learnt and woodenly rendered, clumsy movements and artificial gestures – can breed discouragement. When one considers that in the present case these elements were supplemented by two further factors, namely the amateurishness of a school production and a lack of real motivation on the part of the participants, the full extent of my torment becomes apparent. On the one hand, the cast seemed to believe I knew what I was doing: I fed them the illusions they needed, and they appeared to trust in our ultimate success. On the other hand, when they saw what I saw, they would lose faith and relapse, which meant that standards fell and the temptation returned to give up then and there.

‘We’re wasting our time,’ they would say, ‘we’ll never get anywhere. We’ll only end up looking ridiculous. And even if we do get somewhere, how many performances will we have? One, maybe two. Is all this worth it for just one performance?’

‘Of course it’s worth it,’ I would reply. ‘If it works, it would be worth it just for one moment. Trust me, I know what I’m talking about . . .’ (I was thinking, of course, of the Quartet’s swan song.)

‘Oh, that’s just talk,’ they’d say, shaking their heads and dispersing in mute resignation.

Sometime near the end of April, after months of preparation, endless reassessments, substitutions and changes of mind, countless nervous breakdowns and moments of feverish exhilaration, the play assumed its final shape. It was an hour-long collage of selected scenes and monologues from famous plays – Aeschylus to Beckett. All the World’s a Stage was characterised throughout by the darkest pessimism. It began with the monologue of Prometheus chained to his rock and went on with the dialogue between Creon and Haemon from Antigone; then came a few bitter passages from Shakespeare, among them Jaques’s soliloquy from As You Like It about the seven ages of man, beginning with the words we had adopted as our title; then the concluding soliloquy of Molière’s Misanthrope, followed by Faust’s first soliloquy and a fragment of his dialogue with Mephistopheles. Lastly, there was a fragment of Hamm’s soliloquy from Endgame.

This script, submitted to the school authorities for inspection, was rejected.

‘Why is it so gloomy?’ the deputy headmaster wanted to know, eyeing it with disfavour. Tall, thin, with a sallow complexion and a slightly tubercular look, he was generally known as the Tapeworm. ‘You feel like killing yourself after reading this. We can’t tolerate defeatism in this school.’

‘But these are classics, sir,’ I ventured, trying to defend my creation. ‘They’re almost all in the syllabus. I’m not the one who drew up the syllabus.’

‘Don’t you try to hide behind the syllabus,’ he replied, frowning as he shuffled through the pages. ‘There’s a reason you’ve selected these particular passages: it’s a deliberate attempt to question every decent value and discourage people from study and work. Here, for instance,’ he said, pointing to the page with Faust’s monologue. He read out the first few lines:

The books I’ve read! Philosophy,

And Law, and Medicine besides;

Even (alas!) Theology.

I’ve searched for knowledge far and wide.

And here I am, poor fool, no more

Enlightened than I was before.

‘Well? How else should this be read, in your opinion? It says that studying is worthless and won’t get you anywhere. Doesn’t it? And you expect us to applaud such a message?!’

‘We had it in literature class,’ I retorted impatiently. ‘Are you saying that it’s all right in class or at home, but not on stage?’

‘It’s different in class,’ the Tapeworm replied, unruffled. ‘In class there’s a teacher to tell you what the author intended.’

‘Well, then, sir, what, in your opinion, did Goethe intend here?’ I asked.

‘Isn’t it obvious?’ he snorted. ‘He was talking about pride: excessive,

overweening pride. And arrogance. Just like yours, in fact. Once you start thinking you know everything, you’re bound to come to a bad end. Here you are,’ he said, pointing to a passage further down, ‘it says so here.’

To Magic therefore have I turned

To try the spirits’ power and gain

The knowledge they alone bestow;

No longer will I have to strain

To speak of things I do not know.

‘Well? There you are. Magic, evil powers, pacts with the devil – that’s what happens to the swollen-headed and the proud. But that’s something your script somehow fails to mention. And in any case,’ he said, suddenly changing the subject, ‘why is there no Polish literature represented here? This is a Polish school, after all.’

‘This is a selection from the greatest works in the history of drama –’ I began, but the Tapeworm cut me off in mid-flow and said, in tones of heavy sarcasm, ‘Ah. So you consider, I take it, that our own literature has no drama worthy of note. Mickiewicz, Slowacki, Krasinski – for you they’re small fry, third-rate, second-rate at best . . .?’

‘I didn’t say that,’ I replied. This was an easy thrust to parry. ‘Nevertheless, on the other hand, you must admit that the works of Aeschylus, Shakespeare, Molière and Goethe are performed the world over, while our own classics tend to be appreciated mainly on their home ground.’

‘That’s right – “Exalting the foreign, dismissing your own”, as the saying goes,’ he mocked.

‘Strictly speaking, it’s not a saying; it’s from a poem by Stanislaw Jachowicz, another of our great poets. You know, the one who wrote, “Poor pussy was ill and lying in bed”,’ I supplied helpfully. ‘I’m sure you know it . . .’

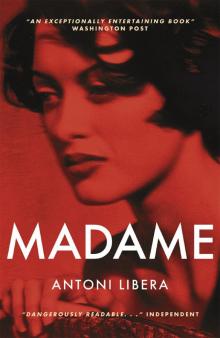

Madame

Madame